Philip Blumel:

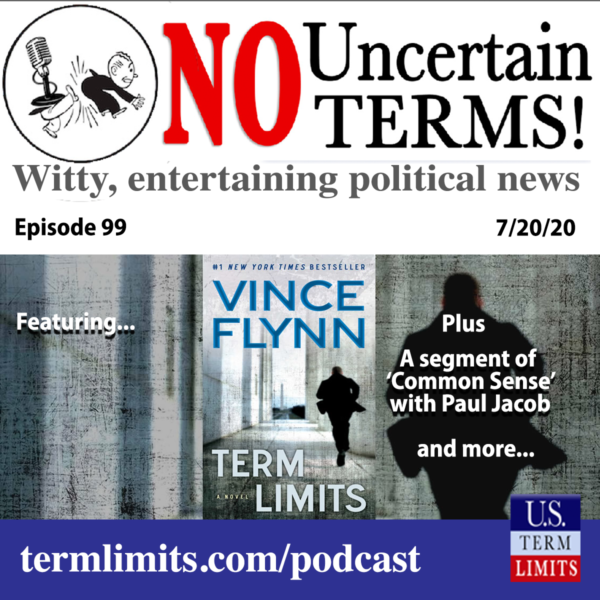

And now for something completely different. Hi, I’m Phillip Blumel. Welcome to No Uncertain Terms, the official podcast of the term limits movement for the week of July 20, 2020.

Stacey Selleck:

Your sanctuary from partisan politics.

Philip Blumel:

Usually on our podcast, we champion citizens efforts to reign in corrupt and overreaching government and revitalize democracy to peaceful institutional reforms, but this week we’re going to step into the fanciful world of shoot first fiction, where term limits of a very different kind have captured the imagination of novelists and readers. Term Limits by Vince Flynn is a fast-paced political action thriller. It’s sort of on the Tom Clancy mold. And in it, a secret group of American ex-commandos published a list of demands and start assassinating Congress members who defy them. Their demands are sort of like what the Club for Growth might make, sand sniper fire, such as reducing spending, freezing taxes, balancing the budget, and my favorite, using zero based budgeting. Well, if those sound like farfetched terrorist demands, just wait until you find out how a corrupt White House decides to fight back.

Philip Blumel:

By the end of that book, you will almost find yourself thinking the terrorists are the good guys, particularly when they issue challenges like this one, “Do not test us again, or we’ll be forced to impose more term limits.” Needless to say, the term limits of the title are not the same kind promoted by this podcast, but that’s not to say there were no real world political lessons in this book. For one example, how about this for a description of a career politician, and by the way, the assassin’s target, which shows how clearly Vince Flynn sees how tenure corrupts over time. “For the last 34 years, he’d survived scandal after scandal and hung onto that seat like a screaming child clutching his favorite toy. Fitzgerald had been a politician his entire adult life, and he knew nothing else. He’d grown numb to the day-to-day dealings of the nation’s capital. The 40 plus years of lying, deceit, deal cutting, career trashing and partisan politics had been so ingrained in Fitzgerald that he not only thought this behavior was acceptable, he truly believed it was the only way to do business.”

Philip Blumel:

The political nemesis of this Fitzgerald politician is a freshman Congressman from Minnesota named Representative Michael O’Rourke, who typifies the well meeting newcomer to Congress. At one point, fiction and fact merge when a journalist announces, “The assassinations have thrust into the spotlight some reforms that the American people have endorsed for some time. The idea of term limits has an approval rating of almost 90%.” They still do, of course, and people are still reading this book and talking about it.

Philip Blumel:

I was recently a guest on a podcast called No Limits, a Mitch Rapp podcast. Its hosts, Chris and Mike, had already done three episodes looking at this book from several angles before they got to me. You can find Chris and Mike’s No Limits podcast on iTunes.

Chris:

Hey guys, I’m Chris.

Mike:

And I’m Mike.

Chris:

And welcome to No Limits, a Mitch Rapp podcast. Today, we welcome Philip Blumel, President of US Term Limits, to our show. And we’d like to thank you for joining us today. Just to start off, can you tell us a little bit more about US Term Limits and your mission and the history of the organization?

Philip Blumel:

Well, we’ve been around since 1991, and our mission basically is to term limit pretty much every office in America of any jurisdiction of any size, but of course the big goal is the US Congress. We have several different strategies to try to do that. In our earlier days, we were behind the move that successfully term limited federal congressmen in 23 states. It’s easy to forget that that even occurred. All of it was done by referendum. And the reason why it’s easy to forget is because in 1995, just two years before the Vince Flynn book was published, we were challenging the Supreme Court in the case US Term Limits versus Thornton, and all of the resolutions that were passed by the 23 states, it didn’t fail anywhere, term limits passed in 23 states, and those referendums were challenged and knocked down all at once by the US Supreme Court in a split decision, five to four. And it was in this context of this turmoil regarding this issue that Vince Flynn was writing his book, Term Limits, because like I said, it was 1995 was the court case and 1997 was when the book was published.

Mike:

Well, we had come to the same conclusion as you around Vince Flynn writing this book in 1997. And we found out it was a late change after the manuscript was written to change to the name Term Limits. And we were wondering-

Philip Blumel:

Oh.

Mike:

Yeah, we were wondering if that’s why the theme wasn’t explored in the specificity in detail we would have liked, referencing the landmark Thornton case, or even referencing state legislatures that had attempted. We thought that would be a really good thing to write into the novel, and we figured out he came late to that name right before the production.

Philip Blumel:

Interesting, because I wondered that too, but I had no idea until just now. And I know in reading it that, now there’s themes in there that absolutely play into major themes of that era, and today, of course, in talking about term limits, but that explains a lot actually. Fascinating.

Mike:

His main antagonist is Senator Fitzgerald, who represents and is an analog in the story for these careerist long term fat cat politicians. The first scene we see is him going back to his house in the middle of the night in a limo, completely hammered, not even respecting his driver. And it says he’s loose with women and he’s loose with drinks. We’re thinking this is one of the power brokers in Washington? So how does your organization work in the real world where that is the challenge? Is that your biggest uphill battle, that a success for you and for term limits would mean those personas in Washington come to an end?

Philip Blumel:

That’s it. I mean, Fitzgerald is a perfect example. I think in the book, he was in politics for over 40 years, the character in the book. Now there’s real world analogs to that, of course, in the US Congress. It’s full of them. And the thing is about it and what we find so unjust and why term limits are so important is that these characters like Fitzgerald, they win their reelection automatically. When they decide that they are going to run for reelection, their campaign coffers start filling with money immediately from special interests. Over 90% of all money from PACs go to incumbents and not challengers. Since 1970, about 94% of the time an incumbent running for their own seat has one. It’s a very safe bet. And once they’re in, you know how they’re going to behave. And for a challenger to fight that is statistically clearly pretty impossible. And the practical reasons why it’s impossible is money.

Philip Blumel:

The challenger has to raise a maximum of $2,800 per person. It’s limited. And of course, they start out well behind the eight ball. When somebody already has power, is in the news every day, everybody knows their name, just getting their name out costs an enormous amount of money, so they start tremendously behind the eight ball. Of course, there’s a zillion other advantages that incumbents have, ranking privilege and everything else. So the point is that someone like that coasts to reelection, that’s obvious, but one thing that might not be obvious to everybody is that there’s of course a lot of people in that district where someone like Fitzgerald is serving that could take that position and do a competent job, but serious goal oriented people aren’t going to run against that incumbent if the success rate of people that do so is basically about 6%. Serious people don’t make bets like that.

Philip Blumel:

You get well meeting naive people running against Fitzgerald’s guy. The gadflies run against Fitzgerald, but it doesn’t work. And so you have two things going on. You have the incumbent has all these advantages, and then you have the challenges, who wisely sit out. They just coast back in and they stay there forever.

Mike:

I like your political and mathematical calculations. I mean, those are odds that no one in Vegas would take. And now we expect our democracy to check itself.

Paul Jacob:

He tries harder. Common sense by Paul Jacob. He’s the Avis Rent a Car of authoritarianism. Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is not the most evil tyrant on the planet. That title clearly belongs to Chinese president Xi Jinping. Instead, Putin is number two. So of course, he tries harder. Two years ago, Xi Jinping got the Chinese Communist Party to jettison his term limits without breaking a sweat, not the slightest pretense of democracy necessary. Two weeks ago, Putin finally caught up with Xi by winning an unnecessary and highly fraudulent national referendum designed to legitimize the constitutional jiggering that would allow him to stay in office until he would be 83 years old, beating Joseph Stalin for post tsar star tsar. So, how did Putin rig the referendum? Voters are being asked to approve a package of 206 constitutional amendments with a single yes or no answer, explained National Public Radio.

Paul Jacob:

Many US states have single subject requirements for ballot measures to prevent precisely this sort of log rolling. Sergei Shpilkin, a well known Russian physicist, produced statistical evidence that as many as 22 million votes, roughly one in four, may have been cast fraudulently, ABC News reported. The European Union regrets that in the run up to this vote, campaigning both for and against was not allowed, read a statement from the 27 nation block. With little debate and scant information, the referendum was just pretense. So why did Putin go through all the trouble to pretend? Low approval ratings, a New York Times piece argued, his lowest level since he first took power 20 years ago. Putin needed all the help that fake democracy can provide without any of those uncomfortable checks on power that real democracy demands.

Paul Jacob:

This is Common Sense. I’m Paul Jacob. For more Common Sense, go to thisiscommonsense.org.

Mike:

Thinking of change agents, such as your organization, and I’m sure the people who have signed your pledge and who work closely with you, in the story we have a young first term Congressman from Minnesota, Michael O’Rourke. He becomes our hero and our protagonist. We learn early that he is taking a very narrow interest in cutting $5 million from the president’s next budget proposal, and he’s sticking to his guns around the rural electrification administration. So, whatever, this small thing, but to him, that’s how government should work. And when the president calls him, he’s even willing to hang up on him and say, “I am not voting for your budget.” He takes it that seriously and has morals that say, “I will do what my constituents want, and I want what’s best. And lowering the debt right now is that.”

Mike:

Do you see any players that are like a Michael O’Rourke who say, “This is not my career. I don’t care about coming back. I will, one, sign onto the pledge with Term Limits, and two, I’m not going to take pressure from the big wigs”? And does that have any lasting effects on either budget or term limits legislation?

Philip Blumel:

Well, such people exist for sure. And we have about 70 people in the Congress right now that have signed our pledge saying that if they’re elected or reelected, that they’re going to sign on and co-sponsor a term limits amendment bill, and they do. But here’s the thing, one or two things happen. One, they go through the process, it’s a seniority system. And if you’re a newbie, you are so far away from those levers of power. So you have two choices, you can be ineffectual and eventually give up, or you can climb that ladder and be in there for 30 years, and by the time you get there, you’re one of them. You’re no longer the Michael O’Rourke, you’re the Fitzgerald.

Mike:

You’re the problem.

Philip Blumel:

You’re the problem. So, that’s why term limits are so vital, because one, you get more competitive elections because open seats are where you get competitive elections. It creates more competitive elections so that you have more chances for a Michael O’Rourke to get in. And then it levels that seniority system where everyone’s sort of in the same boat, and that he has a chance while he’s still Michael O’Rourke, to be in a position where his decisions matter and where his judgment counts and where he has an effect on the legislature.

Mike:

Yeah. So on Michael O’Rourke, he actually has a couple of quotes where it goes a little bit to an extreme. So everything you’re advocating for seems like a great direction for American democracy to cut some of this corruption, but he is seriously contemplating in the book whether the assassins are right or justified.

Philip Blumel:

I know.

Mike:

And the assassins, obviously they take this push for all of their concerns, lowering the debt, something about term limits to an extreme, and say, “We’re going to enforce term limits.” And by that they mean the use of violence and assassination. Even in the book, the Speaker of the House is a target. So how do you feel about this character willing to go so far, thinking about extremism in politics recently, to say, “Maybe Washington is better off this way because at least something’s getting done,” versus your organization, you get something done in a legal and productive manner.

Philip Blumel:

I just might as well say explicitly, the terms limits of the title of this book-

Mike:

It’s fiction.

Philip Blumel:

… refer to something very different than the term limits that are advocated by the organization US Term Limits.

Mike:

Yes, definitely. Definitely. But how can people partner to do this in a constitutional way?

Philip Blumel:

It could be done. First of all, most people are for it. Polling shows that 82% of people in America are for it, including super majorities of Democrats, Republicans and Independent. So this is everybody. So the big problem is, is that there’s two ways to amend the constitution. One of them is of course that Congress itself propose the term limits amendment. Well, of course, it’s contrary to the self-interest of everyone in Congress to do that. So it’s unlikely. And so sometimes even though everyone’s for this and recognizes it’s a good idea, they feel like it just can never occur. Well, our first idea to get around this was to try to have the states do it by referendum and by initiative. And we were part of all of these campaigns across the country back in the ’90s.

Philip Blumel:

Our idea back then, by the way, was that we knew we couldn’t get 50 states to term limit their own congressmen because not all 50 states have the initiative process, but we figured if we got to about half of Congress term limited, then it would be all of a sudden in the self-interest of basically half of that body to term limit the other half. You know what I mean? It would all of a sudden change the power dynamic. That didn’t work because the Supreme Court shut us down. Our new strategy is this. We don’t expect Congress to propose an amendment for term limits itself, but states can do it too. If two-thirds of the states call for an amendment writing convention, states can send delegates, craft and propose an amendment, and then they send that proposal back to all the states at large and ask three-quarters of legislatures to ratify it or not. If they do, it becomes part of the constitution. This is more doable.

Mike:

So that article five strategy of kicking it to the states and relying on them has basically come around because of the Supreme Court decision in ’95.

Philip Blumel:

That’s right. They said we couldn’t do it by referendum.

Mike:

By referendum. So since then, you’ve obviously had some successes, but I noticed there are different versions of term limits being discussed in a lot of the state conventions. And one initiative of you guys is to streamline those into a single document or a single proposal so that the state conventions can be on the same page. Is that correct?

Philip Blumel:

Yeah, that’s pretty much right. Our proposal in the US Congress, to flip back for a second, is six years in the House and 12 in the Senate, not retroactive. And you can come back after sitting out. That’s actually written in bills that are in Congress. But in the convention process, it’s a little different because in the convention process, our constitutional lawyers and we discussed when we went deep into this before we launched this, told us that the convention as viewed by the founders of this country was to be the body that does the proposing, not some outside organization, not the states themselves. It’s the states in convention that make the proposal. What we’re trying to do is have 34 states, which is two-thirds, call for a convention, have delegates sent to the convention, and they can hammer out what the exact details of the proposal would be. So in that sense, yes, we want to get everybody, we want to have this discussion by the states. They would come up with the actual numbers.

Philip Blumel:

We have preferences. We’ll be part of that discussion, but yes, we want to pull together all the states to have that discussion and to nail down what the proposal would be. The effect of term limits comes when it is an institutional reform that is imposed on the entire Congress, where every single seat has a open seat election every six years or eight years or whatever the term limit is, and then you start having competitive elections again. And then you get a lot of these Michael O’Rourkes, or real world versions of him, coming into office. And that’s when you start seeing the real difference made.

Mike:

It would be a job that folks want to do well for their constituents, but not a career that they’re going to get comfortable in.

Philip Blumel:

Yeah.

Mike:

Well, thanks for joining us for this constitutional deep dive into the issue of term limits.

Chris:

And you can find us online at MitchRappPod.com or you can reach out for us on Twitter with the handle of @MitchRappPod. And as always, just let Mitch be Mitch.

Philip Blumel:

Thanks for tuning in to another week of No Uncertain Terms. This week’s action item is for voters in the state of Alabama. The Alabama primary runoff last week saw Auburn football coach and US Term Limits pledge signer, Tommy Tuberville, beat out Jeff Sessions, former attorney general and Senator, to be the GOP nominee for US Senator. Tuberville will face incumbent, Senator Doug Jones, in November. Jones has not signed the US Term Limits pledge committing him to co-sponsor and vote for the congressional term limits amendment. At least not yet. Please go to termlimits.com/DougJones and send a quick message to Doug Jones, providing him with a link to the US Term Limits pledge and urging him to sign it. That’s termlimits.com/DougJones. Remind him that 82% of the people want term limits, including 76% of Democrats. It’s time we put an end to these career politicians in Washington, DC and restore Congress to a body of citizen legislators who actually care about what the people want. Thank you. We’ll be back next week.

Stacey Selleck:

If you like what you’re hearing, please subscribe and leave a review. The No Uncertain Terms podcast can be found on iTunes, Stitcher, YouTube, and now Google Play.

Philip Blumel:

USTL.