By Nicolas Tomboulides

“We have term limits. They’re called elections!”

I’m sure you’ve heard it before. When stale incumbents are confronted with the idea of term limits, they love to trot out this one-liner and accuse term limits supporters of hating democracy. We’re told that elections alone will solve all of government’s ills, if we just give them a chance.

Make no mistake: what you’re hearing is a tactic. The permanent political class — Washington’s interlocking network of lobbyists and corrupt public officials — will stop at nothing to protect the status quo. Long-term members from both parties extort the system for personal gain. They receive lavish perks that most Americans in the private and public sectors never see in their lifetimes. Congress is a sweetheart deal, and the politicians know it. Even with term limits on the table, these insiders will not go quietly into the night.

To understand why elections aren’t term limits, we must first examine the number one determinant of electoral success: money.

On average, incumbents can raise five times as much money as their challengers, amounting to a per-race financial advantage of $588,822. This wouldn’t be a problem if the incumbents worked hard and earned campaign money on merit. Unfortunately, they don’t. Special interest money flows into incumbent coffers purely because a member has filed for re-election, or because they’ve used the aforementioned extortion tactics to shake down a private enterprise.

It adds up. Special interests contribute between 85%-95% of their PAC dollars on average to incumbents, not challengers or open seat candidates. Since 94% of incumbents win re-election, the generosity serves as an investment in favorable treatment down the road. Quid pro quo.

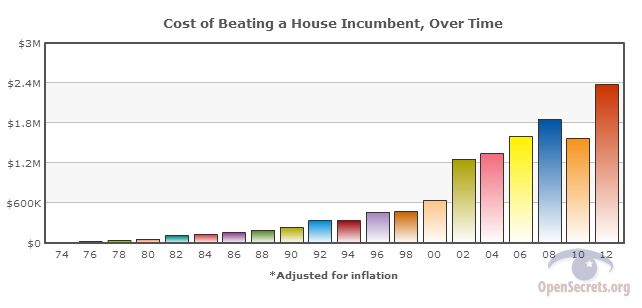

Meanwhile, on the challenger side, candidates have to spend every waking hour begging PACs and members of the community for smaller donations. A well-funded campaign is the only way for an outsider to earn name recognition and the voters’ trust. The Center for Responsive politics estimates the cost of beating a U.S. House incumbent to be $2.5 million. This enormous hurdle keeps most good candidates out of politics.

Many wonder how voters who support term limits could keep re-electing the incumbents they don’t like. On the surface, it’s a paradox, but a closer examination of how elections work provides an explanation. The financial might of incumbents creates a system in which very few citizens can run for office. Even if they’re eminently qualified to serve, they don’t have the connections necessary to successfully challenge a sitting congressman.

This results in having a class of challengers who are, for the most part, not biographically different from the incumbents they oppose. They hail from either big politics, big business or the corrupt nexus between the two. Voters are therefore given the “choice” between the devil they know and the devil they don’t. The lesser of two evils wins, but nothing really changes.

Enter term limits. Congressional term limits honor the right of the people to establish parameters for government service. The 75% of Americans who support them are following in the tradition of those who worked to pass the 22nd amendment, which put term limits on the Presidency.

Term limits shatter the stranglehold that incumbents have on congressional seats. When a long term legislator goes home, he takes his special interest bankroll with him. The result is more competitive, open-seat elections in which all candidates have a fair shot. Data shows that, in rare cases of open seat races, both candidates raise an average total between what incumbents and challengers get today. It’s a happy medium, ideal for legitimate competition.

To answer the age-old question, elections are not term limits. Rather, they are a process that can be improved by term limits. Incumbents would be denied the chance to exploit the system for electoral invincibility. Quality challengers would be given real opportunity, without professional politicians and special interests blocking the door.

Nick Tomboulides is the Executive Director of U.S. Term Limits