Isn’t it an obvious conflict of interest when politicians put a measure on the ballot to weaken or repeal their own term limits?

Isn’t it an obvious conflict of interest when politicians put a measure on the ballot to weaken or repeal their own term limits?

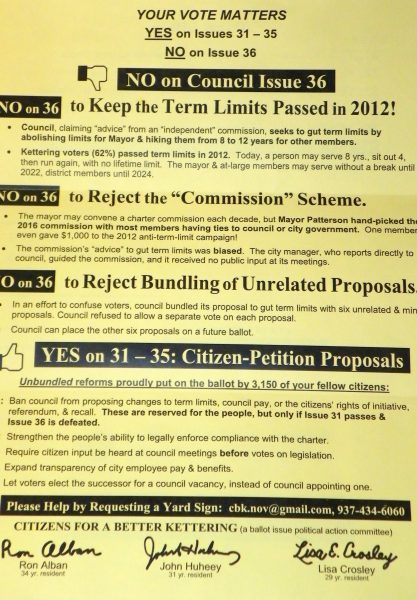

In 2012, citizens of Kettering, Ohio, collected signatures to put an eight-year term limits measure on the ballot. It passed with more than 60% of the vote. In 2016, with a simple council vote, the politicians put an anti-term limits measure, with tricky language, on the ballot in an attempt to undo the recently implemented citizens’ term limits.

This is an old, old story we’ve heard before. If citizens alert their neighbors to the threat in time, these schemes are rarely successful. But typically, a few years later, politicians notoriously attempt to pass it again with new and trickier language, using public resources. And they’re tenacious. They’ll try again and again until they get the answer they want.

And why not? They don’t have to collect signatures in the hot sun or pay money out of their pockets. All the council has to do is vote.

In Nashville, Tennessee for instance, council members, earlier this year, placed an anti-term limits measure on the ballot for the seventh time since voters approved term limits, overwhelmingly, back in 1994. Once again, Nashville citizens shot it down last Tuesday.

But in Kettering, Ohio, citizens didn’t just vote “no” back in 2016. They made a little bit of term limits history. They put an initiative on the ballot that recognized the conflict of interest involved in politicians forcing citizens to defend their term limits law over and over again.

But in Kettering, Ohio, citizens didn’t just vote “no” back in 2016. They made a little bit of term limits history. They put an initiative on the ballot that recognized the conflict of interest involved in politicians forcing citizens to defend their term limits law over and over again.

They put a measure on the ballot that prohibited the council from proposing amendments that seek to alter or abolish any provision in the charter that addresses term limits, their own compensation, or the initiative process. Proposals to change legislation on these topics must come from the citizens themselves. We call it the “conflict of interest initiative.”

This “conflict of interest amendment” passed with 64% of the vote. That’s even higher than the original term limits measure!

The author of this revolutionary idea, Ron Alban, founder of Citizens for a Better Kettering let us know why he initiated the process. According to Alban, “there are many examples of constitution in charters placing limits on government, especially where there’s a history of a power the government has abused and this was simply a specific exercise of the peoples’ right to limit government through their charters and constitutions.”

This conflict of interest amendment also states that any referendum, whether it’s passed by the council or by the citizens, has to be submitted to the voters only at a general election. Alban explains the importance of this is because, as he puts it, “it’s been very, very frustrating to many Ohioans, and elsewhere, where these councils or legislative bodies put important proposals on low-turnout special elections or primary elections.” He continues, “The purpose of that is to try to get it passed by a very small minority of the voters.”

Shady governments do this so they can get their cronies out to the vote and overwhelm the citizens who may not be aware of the self-serving schemes. What this conflict of interest amendment does is makes it clear that anything as important as a charter amendment or a constitutional amendment should go on a high turnout general election.

It is important to mount an education campaign well in advance of the election to assure the voters understand what in this package of proposals from politicians.

According to Albans, the attempt just four years after the term limits were put in place would not have been possible had the anti-conflict of interest language been including in the original bill.

The power of term limits is that it’s easily understood, easy to explain, and something citizens can do. We, at U.S. Term Limits, advise citizens who come to us asking how to launch an initiative to keep it simple: six or eight year term limits, avoiding retro-activity. But the idea of including a conflict of interest provision, as was passed in Kettering, is a good idea to add to standard term limits measures because of the kind of chicanery seen in cities all over America.

While it’s no cost to council members to fool the voters to overturn term limits, it’s a tremendous cost to citizens to initiate a campaign to educate the citizenry that they’re being hoodwinked. Without this provision in place, it has been proven, time and time again, that politicians will use whatever resources it takes, over and over, on the taxpayer dime.

It may be worth adding in conflict of interest language as a standard provision in future term limits initiatives or at least as a relief for beleaguered voters in places like in Nashville where, every couple years, they have to go back and fight the same battle over the term limits law they worked so hard to impose.

Let history show that Ron Alban did it first.

Listen to this conversation and many more on our podcast, episode 14.